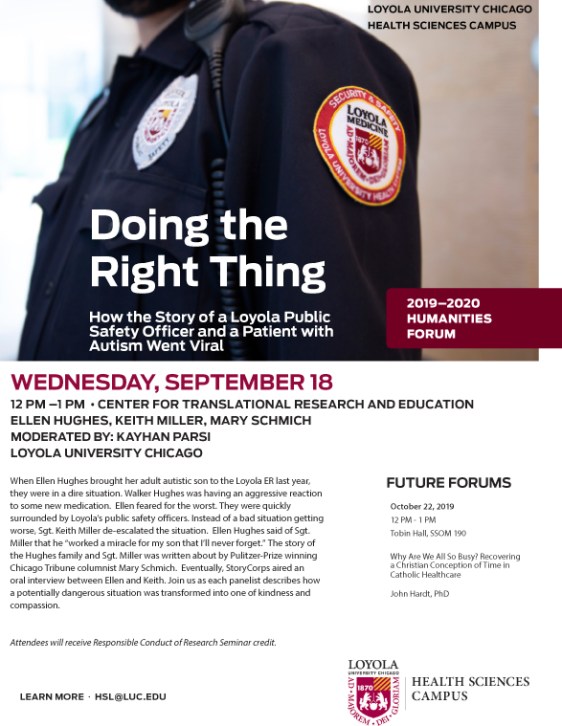

Thanks to the Tribune’s Mary Schmich for bringing much deserved attention to hospital security staff who were ready to help.

by Mary Schmich

2/6/2019

Column: A man with autism, behaving violently, winds up in the ER. The officers on duty respond — by singing and dancing.

Ellen and Robert Hughes expected the worst when they took their son, Walker, who had been on a violent rampage, to Loyola University Medical Center’s ER. But they were inspired by public safety officers, led by Sgt. Keith Miller, left, who calmed him down by singing and dancing.

On the way to the hospital that cold evening, Ellen Hughes sat in the passenger seat of the car, her husband at the wheel, while their son, Walker, sat in back pulling her hair and trying to strangle her.

It had been an awful day. Walker, who is 6-foot-3, has autism and is ordinarily gentle, had been rampaging through the Hughes’ small Chicago home, suffering, they would later learn, from a “paradoxical reaction” to a medicine that was supposed to calm him down.

He had chased his parents through the house, tackled his father to the ground, even bitten him through his winter coat hard enough to hit flesh.

Get to the hospital, a doctor said.

They obeyed, but as they passed the entry doors of Loyola University Medical Center in Maywood, Walker bit his mother’s hand, hard. She screamed, and a phalanx of men in uniform swarmed in.

“Picture it,” she says, “here’s this fragile little mom, the aged parents. Walker’s huge and he’s violently attacking me and suddenly there’s all these cops on him. I’m thinking, ‘My God, they’re gonna kill him.’ ”

They weren’t technically cops. They were the hospital’s public safety officers, but Hughes knew how wrong things could go between a big, violent man with autism and a bunch of uniformed men wearing badges, bulletproof vests and stun guns.

And then things went an entirely different way.

Walker Hughes is 33. His parents, Robert and Ellen, have spent almost that many years in and out of hospitals, trying to help their son while also trying to help others understand autism. In one hospital, Walker was pinned to the floor, screaming. Once, he was handcuffed to a bed, and ever since, even getting him onto a gurney was likely to be a fight.

At Loyola, Ellen prepared for the fight.

“I’m scared to death and I’m bleeding,” she says, recalling that day in late December. “I’m sitting there sadder than I’ve ever been in my life and I hear this game starting up.”

In the cubicle where Walker had been taken for tests and medication, he kept bolting off the examination table. Instead of brutally restraining him, though, the officers tried a different approach each time he jumped up.

As Ellen described the game in a recent blog post:

“Walker gets up!” they cheered.

They helped him sit back down.

“Walker sits down!”

And he did.

“Walker scoots back.”

He did.

“Walker lies down.”

Yes!

For two and a half hours, the officers coaxed and cajoled. They danced. They sang children’s songs. They sang James Brown. They harmonized on the “Mr. Rogers” theme song.

“Walker loved it,” Ellen says. “He was kind of mystified and charmed and started smiling. They were men his size who considered him a real person. It’s scary when people don’t think you’re a real person. You have autism and you can’t talk — but you’re a person. It’s scary to be treated like a lion from the zoo. We’ve been to the doctor and the hospitals a million times and I’ve never seen anything like these guys.”

What Walker experienced might have been different if not for Sgt. Keith Miller, who was on duty at Loyola that night.

“First of all,” he said, when I talked to him Tuesday, “I am the parent of an autistic child myself.”

His experience with his son, who is 14, prompted him to seek training in how to handle patients with autism who arrive at the hospital. Now he helps train other officers. One thing he teaches is that no two people with autism are the same. He found the key to working with Walker, he says, when Walker mentioned Mary Poppins.

“Right then and there, I knew how to deal with it,” he said. “We started singing ‘Mr. Rogers.’ I did ‘Sesame Street’ voices. We made a game. Clapped, cheered. We stayed there for two and a half, three hours. Very few things were more important than Walker.”

Miller says that police and other public safety officers are waking up to the need for such training.

“I think it’s something that’s new, getting bigger and bigger,” he said, “considering that the diagnosis of children with autism is rising.”

After that night, it took Ellen Hughes a few weeks to collect herself well enough to post something about it on social media. She also wrote the hospital asking it to relay her thanks to the officers.

“You can’t train that kind of spirit,” she says.

Walker is getting good care now and recovering from the wrong medication. Ellen’s hand still hasn’t healed from the bite, but something in her was restored that night.

read on Tribune site

mschmich@chicagotribune.com

Twitter@MarySchmich

And, a Follow-up Tribune Column:

by Mary Schmich

2/9/2019

Column: Sgt. Keith Miller and his crew hailed as heroes

‘I’ve learned that the autism community is much larger than I could have ever imagined’

Sgt. Keith Miller stands outside Loyola University Medical Center in Maywood on March 7, 2019. In late December, he and his crew helped patient Walker Hughes, a man with autism who was having a violent reaction to medication, by singing and dancing to calm him down without force. (Abel Uribe/Chicago Tribune)

For the past month, Keith Miller has been overwhelmed by thank-yous.

From all over the country, parents of children with autism have said thank you. His bosses have said thank you. A woman from Canada expressed her gratitude by sending a box of socks and Canadian candy.

He has heard from national and local media. He has been invited to speak. He has been hailed as a hero.

And all of it because one night he put on his security guard’s uniform, went to work and, in his view, just did his job.

“It’s very, very surprising, and humbling,” Miller said this week when I called to talk about the response to the story of what happened one night in late December at Loyola University Medical Center in Maywood.

Last month, I recounted that story in a column, about how Miller was the sergeant in charge of the security team on the night Walker Hughes arrived in the ER.

Hughes, who is 33 and has autism, was in the midst of a violent reaction to his medication, and as he entered the hospital, he bit his mother. The security guards swarmed. Walker’s mother, Ellen Hughes, remembers thinking, “They’re going to kill him.”

But where others might have seen merely a menace, Miller and his crew — he’s quick to say that if there’s credit to be had, they all share it — saw a man in need of help. Instead of restraining him with force, they calmed him down with songs, dancing and games.

In some ways what happened that night was not remarkable, just another slice of chaotic life in the ER. But hundreds of thousands of people have now heard about the incident, and to many of them it was remarkable that these men in uniform responded with compassion instead of aggression.

From the flood of response, Miller has learned a lot.

“I’ve learned that the autism community is much larger than I could have ever imagined,” Miller said, “that a lot of parents out there are struggling with the same issues. I also learned that a lot of health care organizations aren’t prepared to deal with this. I learned that law enforcement isn’t prepared to deal with the generation with autism coming up. I’ve learned also how fast this issue has affected people.”

The affected people include him.

Miller grew up in Chicago’s Englewood neighborhood, the youngest of four kids raised by their mother. She was the kind of mom, he says, who cooked and babysat for neighbors in need, and she instilled in him the spirit of helping. One of her friends had a son with muscular dystrophy, so Miller spent most nights at the boy’s house, bathing him, lifting him off and on the toilet, helping him into bed. It wasn’t duty, he said, it’s what you do when you care.

“It prepared me to be a lot more compassionate,” he said. “It molded me and prepared me to deal with my son.”

Miller’s son, Cameron, was 12 months old when Miller and his wife began to suspect a problem.

Sgt. Keith Miller stands with his son, Cameron, who is 14 and has autism. (Family photo)

“He stopped walking, stopped saying bye-bye and making eye contact, started doing the hand-flapping,” Miller said. “We didn’t know what was wrong.”

He was so unaware of autism that when he first heard his son’s diagnosis, he wondered if it meant his child was gifted.

But he and his wife soon learned the truth, and they adjusted their lives to help their son. It was that personal experience, along with some professional training in how to handle people with autism, that guided his response to Walker Hughes.

In the weeks since the story went public, the Hughes family, too, has been overwhelmed with inquiries and kindness, much of it from other families who deal with autism.

“There’s a lot of us,” Ellen Hughes said.

Miller and Hughes hadn’t seen each other since that night in the ER until they were both invited to a recent radio interview. She was struck by how gentle, friendly and dedicated he was and afterward wrote to suggest I talk to him some more.

“He’s amazing and full of stories you will really appreciate,” she said. “And not full of himself.”

As for her son Walker, he has spent most of his time since December in a care facility in the hopes of having his medication regulated. His parents brought him home for a few days recently.

“He was darling, charming, talking to us — and then, suddenly, completely violent and strange,” she said.

She and her husband, Robert, called 911. When the officers arrived, Walker was shouting and pounding on a table.

“I pointed out to Walker that these were officers, just like his friends in the Loyola ER that he had fun with,” she said. “He took a good look at them, got up, put on his jacket, walked down and got in the ambulance. Amazing. I totally credit this to Sgt. Miller and his crew.”

The number of children diagnosed with autism has risen dramatically in recent years. Those children will grow into adults. The children and the adults will need care that as a society we don’t yet provide.

But it starts with the individuals like Keith Miller who know it matters.

read on Tribune site

mschmich@chicagotribune.com

In recent years, our appreciation of people unlike us – especially those from what our hateful President calls ‘s—hole countries’ – shifted into high gear when our son Walker, now in his 30’s, moved into Elaine House, a Clearbrook group home for guys with autism staffed mostly by newly-arrived African immigrants.

In recent years, our appreciation of people unlike us – especially those from what our hateful President calls ‘s—hole countries’ – shifted into high gear when our son Walker, now in his 30’s, moved into Elaine House, a Clearbrook group home for guys with autism staffed mostly by newly-arrived African immigrants.

Like all autism parents, especially those with jumpy, nonverbal, 6’3” guys like our son Walker, my husband Robert and I can easily imagine how things often go very wrong very quickly when the police get involved.

Like all autism parents, especially those with jumpy, nonverbal, 6’3” guys like our son Walker, my husband Robert and I can easily imagine how things often go very wrong very quickly when the police get involved.

Betsy DeVos displayed at best confusion and at worst a lack of knowledge about a key federal law involving students with disabilities during her Tuesday confirmation hearing before a Senate panel that will vote on whether she should become President-elect Donald Trump’s education secretary.

Betsy DeVos displayed at best confusion and at worst a lack of knowledge about a key federal law involving students with disabilities during her Tuesday confirmation hearing before a Senate panel that will vote on whether she should become President-elect Donald Trump’s education secretary.